5.5. Modules#

As we write more and more functions to accomplish specific cryptography tasks, copying/pasting each function into each new notebook will get cumbersome. Instead, we can save our commonly used functions into a Python file that we can import into each notebook as needed. These files are referred to as modules.

Creating a Module#

To create a module you need to create a Python script file. A script file ends in .py and contains only Python code without all the Markdown and structure that a Jupyter Notebook provides. To do this in your Jupyter Notebook, perform the following steps from your Home Directory:

Click

[New]then[Text File]

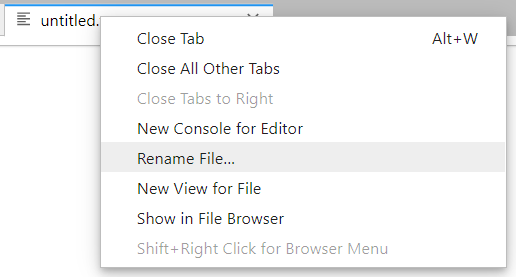

Click on

untitled.txtto rename the file

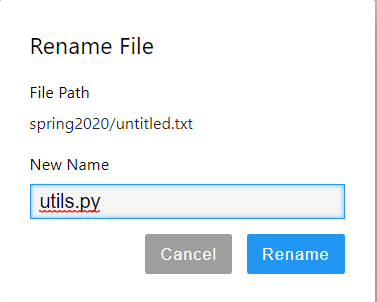

Rename the file so it ends in

.py.

Copy / Paste all Python code into your module that you’ll want to access in other Notebooks.

Save your file before closing the tab or window.

In this example, the functions text_clean and caesar have been copied into the file utils.py.

Importing a Module#

Now that you have your module file saved, you can import the contents into any other notebook that is stored in the same folder as the module. There are a few ways you can import the module depending on how you want to use it:

Method 1#

import utils

This method is the easiest to understand. Use import followed by the name of your module file (without the .py). To use the objects found inside the module, the general structure is moduleName.objectName. So, to use the textClean() function inside module toolkit:

print( utils.text_clean('Test Message') )

TESTMESSAGE

Trying to directly call text_clean will result in an error, since it won’t know where to find that function without the utils. prefix.

print( textClean('Test Message') )

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-10-f66b8a0326dc> in <module>

----> 1 print( textClean('Test Message') )

NameError: name 'textClean' is not defined

Method 2#

Since typing utils a lot when working with the module could get tiring, there are a few ways to make this easier. One is to let your current Notebook use a different name than the filename of the module. In this example, we import utils as tk which is short for “toolkit”.

import utils as tk

print( tk.caesar('Test', 7) )

ALZA

Method 3#

If you really can’t stand to type a little extra, you can pull the functions from a module into your Notebook so you can use them natively without any prefix. The syntax is from [module-name] import [list, of, objects, to, import]

from utils import text_clean, ceasar

print( text_clean('This is Pretty Lazy, but it works') )

THISISPRETTYLAZYBUTITWORKS

Method 4#

This is somewhat of a “everything but the kitchen sink” approach.

from utils import *

This is generally considered bad practice, since you will import everything in the utils.py file, and you may not know what’s in there! Doing so will import everything inside the module including functions, objects, etc into your Notebook. This is bad because:

It could take a long time or use up a lot of memory

It could overwrite variables or functions of the same name in your Notebook

If you didn’t write the module, you don’t know what it’s importing

You’ll see this method used on Graded Homework assignments due to some quirks in the Gradescope auto-grader, but in general you should use Methods 1-3 when possible.

Publicly Available Modules#

Over time people have developed really powerful modules that can do tasks far beyond what a novice programmer could accomplish. Collections of modules can be grouped together in what are known as packages. Instead of keeping these modules to themselves, the Python Software Foundation has set up a publicly accessible database of packages, found at https://pypi.org. We’ll use a few of these packages in this course to generate bar charts, generate random numbers, and apply hash functions.